When you fill a prescription for a generic drug, you might assume all generics are the same. But that’s not true. There are two very different kinds of generics on the market: authorized generics and first-to-file generics. And the difference between them can mean big savings-or big missed savings-on your prescription costs.

What’s the difference between authorized generics and first-to-file generics?

An authorized generic is the exact same drug as the brand-name version. It’s made by the same company that makes the brand, on the same生产线, with the same ingredients, and the same packaging-except it doesn’t have the brand name on it. Think of it like a store-brand soda made by Coca-Cola. It’s Coke, but sold under a different label.

A first-to-file generic is made by a different company that was the first to submit an application to the FDA to copy a brand-name drug. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, this company gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version before anyone else can enter the market. This exclusivity is meant to reward the company for taking the legal and financial risk of challenging the brand’s patent.

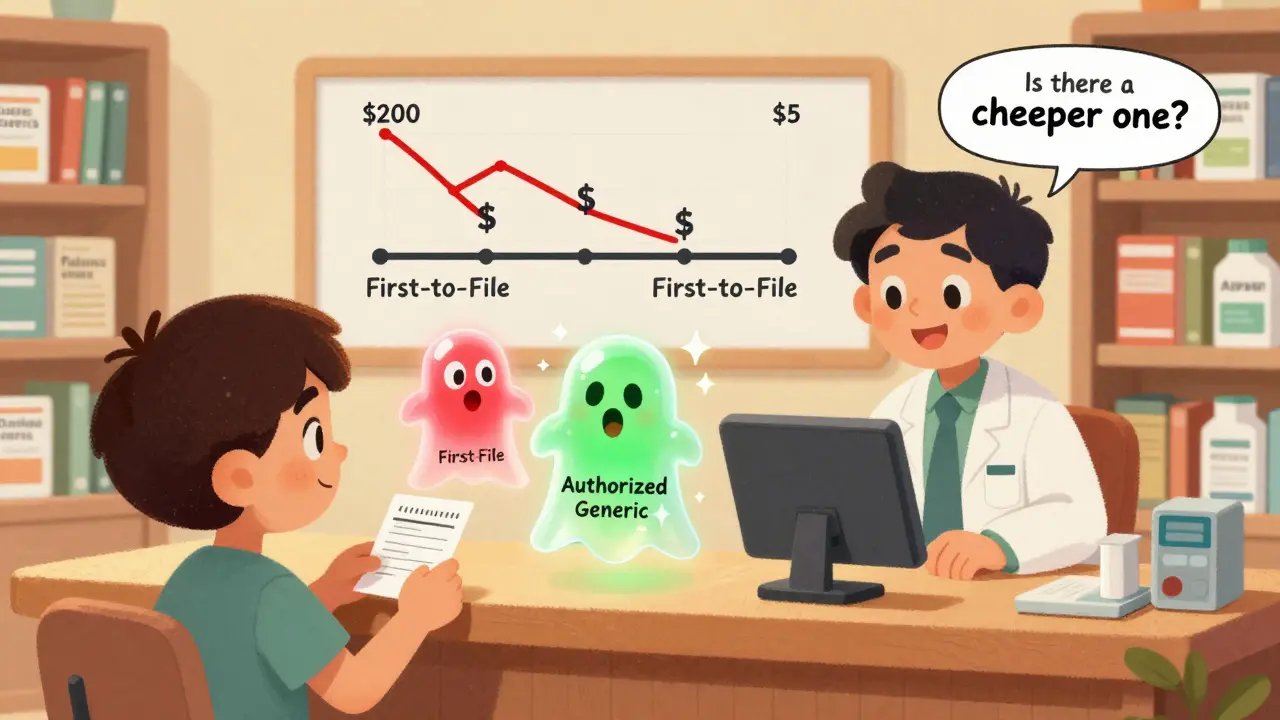

Here’s the twist: the brand-name company can launch its own authorized generic during that 180-day window. That means two versions of the same drug-both generics-are now on the market at the same time. And that’s when prices really start to drop.

How much cheaper are authorized generics compared to first-to-file generics?

The data from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) shows clear patterns. In markets where only the first-to-file generic is available, the price of the generic is about 14% lower than the brand-name drug at the retail level. But when an authorized generic joins the market during that 180-day exclusivity period, the discount jumps to 18%-a 4 percentage point increase in savings.

At the wholesale level, the difference is even bigger. Pharmacies pay 20% less than the brand price when only the first-to-file generic is sold. But with an authorized generic in the mix, that discount climbs to 27%. That’s a 7-point swing-meaning pharmacies can buy the drug for nearly a third less than the brand.

One study found that when an authorized generic enters the market, retail prices for the generic drop by 4% to 8%, and wholesale prices fall by 7% to 14%. That might not sound like much, but for a drug that costs $200 a month, that’s $8 to $28 saved per prescription-every month.

Why does this matter for pharmacies and patients?

It’s not just about what you pay at the counter. Pharmacies make more profit when there’s more competition. When the first-to-file generic enters, pharmacy profits go up. But when an authorized generic joins in, those profits go up even more. That’s because the two generics undercut each other on price, and pharmacies can negotiate deeper discounts.

Patients benefit directly. In markets with both generics, you’re more likely to get the lowest possible price. Some insurers even require you to choose the cheapest generic available-and that’s often the authorized one.

Here’s the catch: if you’re handed a first-to-file generic without knowing an authorized version exists, you might be paying more than you need to. Pharmacists aren’t always required to tell you which version they’re dispensing. So if your copay feels higher than expected, ask: “Is there a cheaper generic available?”

What happens after the 180-day exclusivity ends?

Once the first-to-file company’s exclusivity expires, other generic makers can enter. And when more than one generic is on the market, prices plunge. The FDA found that when two generics compete, prices drop 54% below the brand price. With four generics, it’s 79%. With six or more, prices fall over 95%.

But here’s where it gets interesting: even after the 180 days, the presence of an authorized generic during that window has a lasting effect. The FTC found that the first-to-file company’s revenues stayed 40% to 52% lower for up to 30 months after their exclusivity ended. That’s because patients and pharmacies got used to the lower prices. Once you’ve paid $10 for a pill, you’re not going back to $20-even if the brand tries to re-enter the market.

Do authorized generics hurt innovation?

Some people worry that if brand companies can launch their own generics, they’ll discourage other companies from challenging patents. After all, why risk millions in legal fees if the brand might just flood the market with its own cheaper version?

But the FTC looked at this closely. Their analysis of hundreds of drugs showed no measurable drop in the number of patent challenges by generic companies. Even with authorized generics in the mix, companies kept filing ANDAs. Why? Because the 180-day exclusivity period is still worth hundreds of millions of dollars. That’s a powerful incentive.

Dr. Robin Feldman, a pharmaceutical policy expert, put it plainly: “The 180-day exclusivity period can be worth several hundred million dollars.” That’s not something a brand’s authorized generic easily wipes out. The market still rewards bold generic challengers.

What about the long-term? Are authorized generics here to stay?

Yes. And they’re becoming more common. About 20% of authorized generics launched between 2010 and 2014 had no sales in Medicare data after five years-but that doesn’t mean they failed. It means they did their job: they drove prices down fast, and then faded as cheaper, non-authorized generics took over.

The FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), updated in 2022, have made it faster and cheaper for any company to get a generic approved. Approval times have dropped by 13 months on average. That means more competitors enter sooner. But authorized generics still play a key role in the early phase-when prices are highest and competition is lowest.

Brand companies use authorized generics strategically. Sometimes they launch them as part of a legal settlement to avoid a long court battle. Sometimes they do it to protect their market share. Either way, it’s not charity-it’s business. But for you, the patient, it’s a win.

What should you do as a patient?

Don’t assume your generic is the cheapest option. Ask your pharmacist: “Is this a first-to-file generic, or is there an authorized generic available?” If you’re paying more than $15 for a generic that’s been on the market for over a year, you’re probably overpaying.

Check your insurance formulary. Some plans list authorized generics separately-and they’re often the lowest tier. If your plan doesn’t distinguish them, ask for a price match. Many pharmacies will lower your copay if you show them a lower price elsewhere.

And if you’re on a chronic medication-like high blood pressure, cholesterol, or diabetes-consider switching to mail-order or bulk discounts. With generic prices this low, buying a 90-day supply often cuts your cost even further.

The bottom line: authorized generics aren’t just another type of drug. They’re a powerful tool that drives prices down faster. And if you know how to use them, you’ll pay less every month-without sacrificing quality or safety.

12 Comments

Just found out my blood pressure med is an authorized generic-saved me $22/month. I had no idea this even existed. Thanks for breaking it down like this.

Now I’m checking all my prescriptions.

Why isn’t this common knowledge?

This is wild. I’ve been paying $45 for my cholesterol pill for years. Just called my pharmacy-turns out there’s an authorized version for $9.

I’m crying.

Thank you.

OMG I just realized I’ve been getting ripped off my whole life. This is why America is broken. Big Pharma is stealing from us. I’m so mad right now. I need to post this everywhere.

Someone call the news!

Let me be unequivocally clear: this is not merely a market inefficiency-it is a systemic betrayal of public trust. The Hatch-Waxman Act was intended to foster competition, not to enable monopolistic collusion under the guise of ‘authorized’ alternatives. The FTC’s findings are not incidental-they are indictments. And yet, patients remain ignorant, pharmacists remain silent, and insurers remain complicit. Where is the outrage? Where is the legislative response? This isn’t about savings-it’s about justice.

And if you’re not demanding transparency, you’re enabling exploitation.

wait so authorized generic = brand but no logo? so its like buying a nike shirt with no swoosh? but still same fabric?

that sounds scammy.

This is one of those rare moments where capitalism actually works for the consumer 😊

Bravo to the FTC for uncovering this. And kudos to you for sharing it so clearly!

Knowledge is power-and power to save money is power to live better.

Let’s spread this like wildfire. Share it with your grandma, your coworker, your local community board.

Every person who understands this is one less person getting overcharged.

Small wins matter. This is one.

I used to think generics were all the same until I got hit with a $60 copay for a drug that should’ve been $12.

Turns out I was getting the first-to-file. My pharmacist didn’t say a word.

I felt like a sucker.

Now I ask. Every time.

And I don’t care if they roll their eyes.

I’m not paying extra for a label.

so like… if the brand makes the generic… aren’t they just tricking people into thinking its cheaper? like… its still them?

kinda feels like they’re playing both sides…

but also… i’m saving money so idk man.

You know, this whole thing reminds me of how we think about food labels-organic, non-GMO, free-range-it’s all about perception, right? But here, the perception is flipped. We assume ‘generic’ means ‘inferior,’ but when you realize the authorized version is literally the same pill, same factory, same everything-just without the fancy branding-it’s almost poetic. It’s like the drug industry finally admitted: the name doesn’t matter. The science does. And maybe, just maybe, that’s the most radical thing about all of this. We’ve been conditioned to pay more for a logo, and now we’re being offered the truth: you don’t need the logo to get the healing. The healing was always there. We just had to stop paying for the packaging. And that… that’s a quiet revolution.

Why are we letting foreign companies make our drugs? This is a national security issue. If the U.S. can’t even make its own generics without outsourcing, what’s next? Who’s controlling our medicine? This is weak.

Can someone clarify: does the authorized generic always appear during the 180-day window, or is it optional for the brand company? Is there data on how often this happens? I’d like to see the percentage of drugs where this tactic is employed.

This is one of those topics that should be taught in high school economics-right next to supply and demand. The beauty here is that competition, even manufactured competition, forces prices down. The brand company isn’t being altruistic; they’re hedging. But the result? You and I pay less. That’s not a loophole-it’s a feature of a functioning market. The fact that we didn’t know this speaks volumes about how opaque the pharmaceutical system is. So thank you. Not just for the data-but for making it feel human. I’m telling my mom tonight.