Every year, thousands of patients in the U.S. receive the wrong medication-not because of a mistake in the prescription, but because the pharmacy mixed up who the patient was. It sounds impossible, but it happens more often than you think. The fix? Simple, proven, and required by law: using two patient identifiers before handing out any prescription.

Why Two Identifiers? The Real Risk

Imagine this: two patients walk into the same pharmacy on the same day. One is Mary Johnson, 68, taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. The other is Mark Johnson, 69, taking aspirin for heart disease. Same last name. Similar age. Same pharmacy. If the pharmacist only checks the name, the risk of giving Mary Mark’s pills-or worse, giving Mark a blood thinner he doesn’t need-is real. This isn’t hypothetical. According to The Joint Commission, patient misidentification causes nearly 20% of all serious medication errors in hospitals and pharmacies. And it’s not just about names. Patients with common names, similar birthdays, or those who’ve moved and changed their records can easily get lost in the system. One study found that up to 10% of dangerous drug interactions go undetected simply because systems can’t link a patient’s full history across different providers. The solution isn’t fancy tech-it’s discipline. Use two pieces of information that belong only to that person. Not just the name. Not just the date of birth. Both.What Counts as a Valid Identifier?

Not everything you think is a patient identifier actually counts. The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG.01.01.01) is clear: only certain data qualify.- Accepted identifiers: Full legal name, assigned medical record number, date of birth, phone number, or a unique patient ID assigned by the healthcare system.

- Not accepted: Room number, bed number, location, or any information that could be shared by multiple patients.

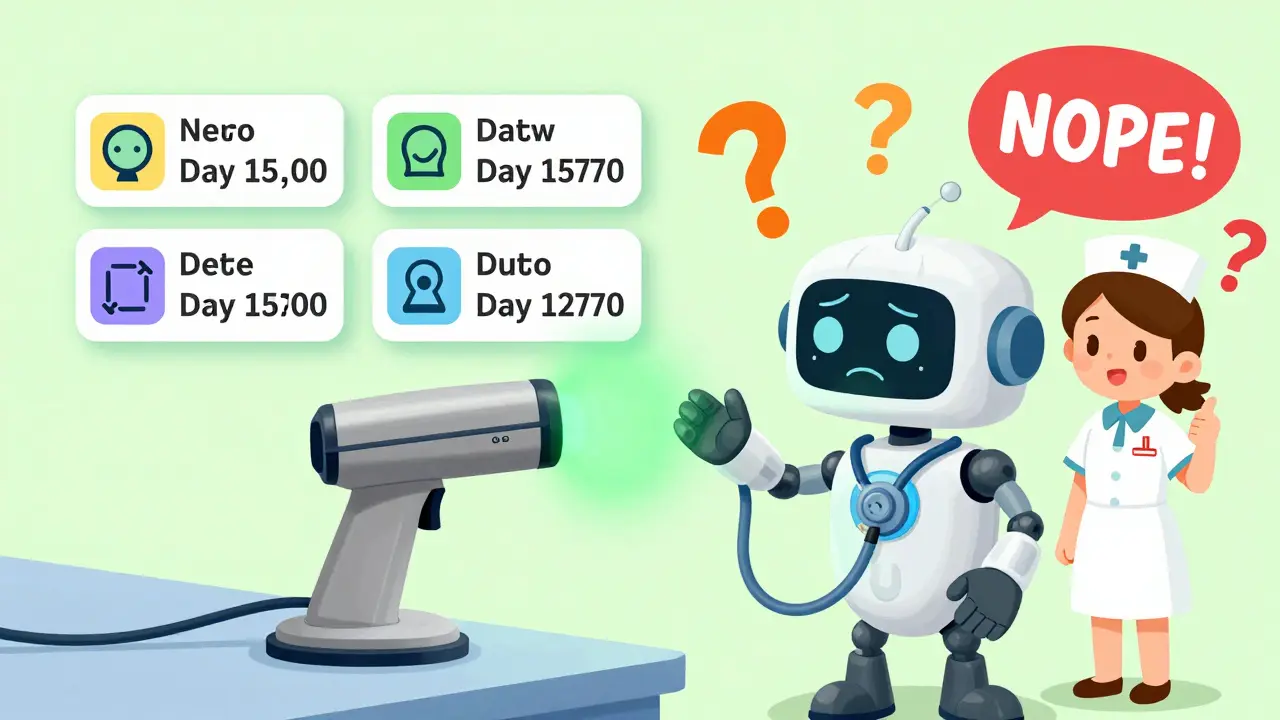

Manual vs. Tech: What Actually Works?

You might think, “I just ask for name and DOB. That’s enough.” But manual checks have a flaw: humans get tired. They get busy. They skip steps. A 2023 survey of 1,200 pharmacists found that 63% admitted to occasionally cutting corners during peak hours. In community settings, 42% said they rarely document the verification-meaning there’s no record if something goes wrong. Technology changes the game. Barcode scanning, when used correctly, cuts medication errors by 75%. Here’s how it works:- Pharmacist scans the patient’s wristband (with barcode containing name and MRN).

- System cross-references the medication label with the patient’s profile.

- If there’s a mismatch-wrong drug, wrong dose, wrong person-the system flags it immediately.

The Hidden Danger: Duplicate Records

One of the biggest silent killers in patient safety is duplicate medical records. A patient gets treated at three different clinics. Each one creates a separate record. No one links them. The result? A patient with diabetes gets prescribed a new drug that interacts with a medication they’re already taking-because the second doctor never saw the first record. A case from Altera Health in 2024 showed a woman admitted for severe fatigue. Doctors couldn’t find her history. She was given a new set of tests, new meds-and almost received a drug she was allergic to. Only after days did they find her original record under her middle name. This is where Enterprise Master Patient Index (EMPI) systems come in. They act like a central filing cabinet that pulls together all a patient’s records, no matter where they’ve been treated. Hospitals without EMPI systems have 8-12% duplicate records. That’s not a glitch-it’s a systemic failure. And it’s expensive. Each large hospital loses an estimated $40 million a year just cleaning up these errors.What Happens When You Don’t Follow the Rules?

This isn’t just best practice-it’s mandatory. The Joint Commission makes compliance with two-identifier verification a condition for hospital accreditation. In 2023, non-compliance was the third most common violation in hospital surveys, accounting for 28% of all patient safety goal failures. Lose accreditation, and you lose Medicare and Medicaid payments. That’s not a fine. That’s financial suicide for a pharmacy or hospital. The 21st Century Cures Act and CMS rules now tie patient identification directly to interoperability. If your system can’t reliably identify patients, you can’t share data with other providers. That means fragmented care, delayed treatment, and higher risk.

How to Implement This Right

You don’t need a billion-dollar system to get this right. Start small, but start now.- Train staff daily: Make it part of every shift. Role-play scenarios. Don’t just hand out a policy document.

- Use tech when you can: Even a simple barcode scanner on the counter can cut errors in half.

- Document everything: The Joint Commission found that 37% of non-compliant pharmacies didn’t record the verification. If it’s not written down, it didn’t happen.

- Use timeouts for high-risk meds: Before giving insulin, heparin, or chemotherapy, pause. Say the name. Say the DOB. Scan the wristband. Confirm the drug. Then give it.

What’s Next? The Future of Patient ID

The U.S. is moving toward a voluntary national patient identifier. A pilot program launched in January 2025 in five regional health exchanges is testing a system that assigns each person a unique, encrypted ID-like a Social Security number for health records, but safer and private. If it works, it could eliminate duplicate records entirely. It could make it impossible to give a drug to the wrong person-not because someone remembered the right name, but because the system just knew. But until then, the answer is simple: use two identifiers. Every time. No shortcuts. No exceptions. Patients don’t need fancy gadgets. They need you to slow down, confirm, and care enough to get it right.Frequently Asked Questions

What are the two patient identifiers required by law in pharmacies?

The Joint Commission requires at least two patient identifiers that are specific to the individual: full name and date of birth are the most common. Other acceptable identifiers include medical record number, phone number, or assigned patient ID. Room number, bed number, or location are never acceptable.

Is asking for name and DOB enough to prevent errors?

It’s the minimum requirement, but not always enough. Human error, similar names, and incomplete records can still cause mistakes. Technology like barcode scanning adds a layer of verification that catches mismatches even when staff make a mistake.

Why can’t I use room number or location as an identifier?

Room numbers change. A patient might be moved for surgery, transferred to another unit, or even discharged and readmitted. Relying on location means you’re verifying where someone is-not who they are. That’s not safe.

What happens if a pharmacy doesn’t use two identifiers?

The pharmacy risks losing accreditation from The Joint Commission, which can lead to loss of Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement. It also increases the risk of serious medication errors, which can cause harm or death to patients. Non-compliance is one of the top three violations in hospital surveys.

Can biometric scanners replace name and DOB?

Biometric systems like palm-vein scans are highly accurate and can be used as one identifier-but they should still be paired with a second, human-readable identifier like name or date of birth. This ensures that if the system fails, staff can still verify identity manually.

How do duplicate medical records contribute to pharmacy errors?

Duplicate records mean a patient’s full medication history isn’t visible. A patient might be allergic to a drug in one record, but that allergy isn’t linked to their other records. When a pharmacist fills a prescription, they might not see the warning-and the patient could be given a dangerous medication.

Is double-checking by two pharmacists effective?

Research shows no strong evidence that having two people check a medication reduces errors unless the process is standardized and tracked. Often, double-checking becomes a formality. Technology-based verification is more reliable because it doesn’t depend on human attention.

What should a pharmacy do if a patient can’t provide their date of birth?

If a patient can’t communicate, verify identity using a family member or legal representative with proper documentation. If that’s not possible, use a unique identifier like a medical record number from the patient’s wristband or electronic record. Never guess or assume.

12 Comments

Man, I’ve seen pharmacists just glance at the name and hand over the script like it’s a coffee order. Scary stuff. I had a cousin almost get the wrong meds last year-turns out the system mixed her up with someone else with the same last name. Glad this post exists. We need more of this awareness.

I work in a small clinic in rural Texas. We don’t have barcode scanners, but we started using a simple checklist above the counter: Name + DOB + Confirm. It’s not fancy, but it’s made a difference. Staff used to skip it during rush hour. Now? They remind each other. Small changes matter.

The systemic failure of duplicate medical records is arguably the most insidious problem in American healthcare infrastructure. The absence of a unified patient identifier forces providers to rely on probabilistic matching algorithms that fail with alarming frequency-particularly when patients have common names, non-standard spellings, or have relocated across state lines. The 8–12% duplicate record rate cited isn’t a statistical anomaly; it’s a structural flaw baked into the architecture of our fragmented EHR ecosystem. Until national interoperability standards mandate deterministic identity resolution, we’re merely rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Let’s be real-this isn’t about safety. It’s about liability. Hospitals push ‘two identifiers’ because lawyers told them to, not because they care about patients. And don’t get me started on ‘biometric scanners.’ They’re just another way for vendors to sell overpriced junk while the system stays broken. Meanwhile, the real problem-understaffed, overworked pharmacists-is ignored. You don’t fix human collapse with tech glitter.

Just saw a pharmacist today use name + DOB + wristband scan. Didn’t say a word. Just did it. That’s the culture we need. No fanfare. Just discipline.

I appreciate the emphasis on documentation. Too often, verification is assumed because it’s ‘common practice.’ But if it’s not recorded, there’s no accountability. In our pharmacy, we now use a digital checkbox in our workflow system that requires initials and timestamp. It’s simple, but it’s changed our compliance rate from 62% to 98% in six months.

As someone who’s worked in both urban and rural pharmacies, I’ve seen how culture affects safety. In cities, people are rushed. In small towns, they know everyone by face-but that’s dangerous too. I once had a patient come in for her grandson’s meds. She said, ‘It’s Jimmy’s.’ I asked for his DOB. She didn’t know it. We called the family. Saved a potential disaster. Trust is good. Verification is essential.

Two identifiers? That’s just the tip. The real agenda? The federal government is quietly building a national ID system under the guise of ‘patient safety.’ Biometrics, EMPI, encrypted SSN-alternatives-they’re all stepping stones to a centralized health database. They say it’s for ‘efficiency.’ But once they have your full medical history tied to a single ID, who controls it? Who audits it? Don’t be fooled. This isn’t about safety-it’s about control.

In India, we don’t have fancy scanners. But we use name, father’s name, and address. It works. Because in our culture, family matters. Maybe we don’t need tech. Maybe we just need to remember: people are more than a barcode.

name + dob = ✅

scan = 🤖

but what if the system glitches? 😳

we still need humans. don’t let tech make us lazy. 🙏

My grandma used to say, ‘If you’re in a hurry, you’re doing it wrong.’ That’s pharmacy right there. I’ve seen nurses yell at pharmacists for ‘taking too long’ to verify. But guess what? The ones who take the extra 10 seconds? They’re the ones who don’t end up on the news. Slow is safe. Always.

Compliance with NPSG.01.01.01 remains a non-negotiable standard of care. Failure to implement dual verification protocols constitutes a breach of the duty of candor and constitutes a material deviation from the standard of practice in ambulatory and institutional pharmacy settings.