AMD Risk Assessment Tool

How Your Risk Factors Influence AMD Risk

This tool estimates your relative risk of developing age-related macular degeneration based on factors discussed in the article. Note: This is a conceptual tool for educational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice.

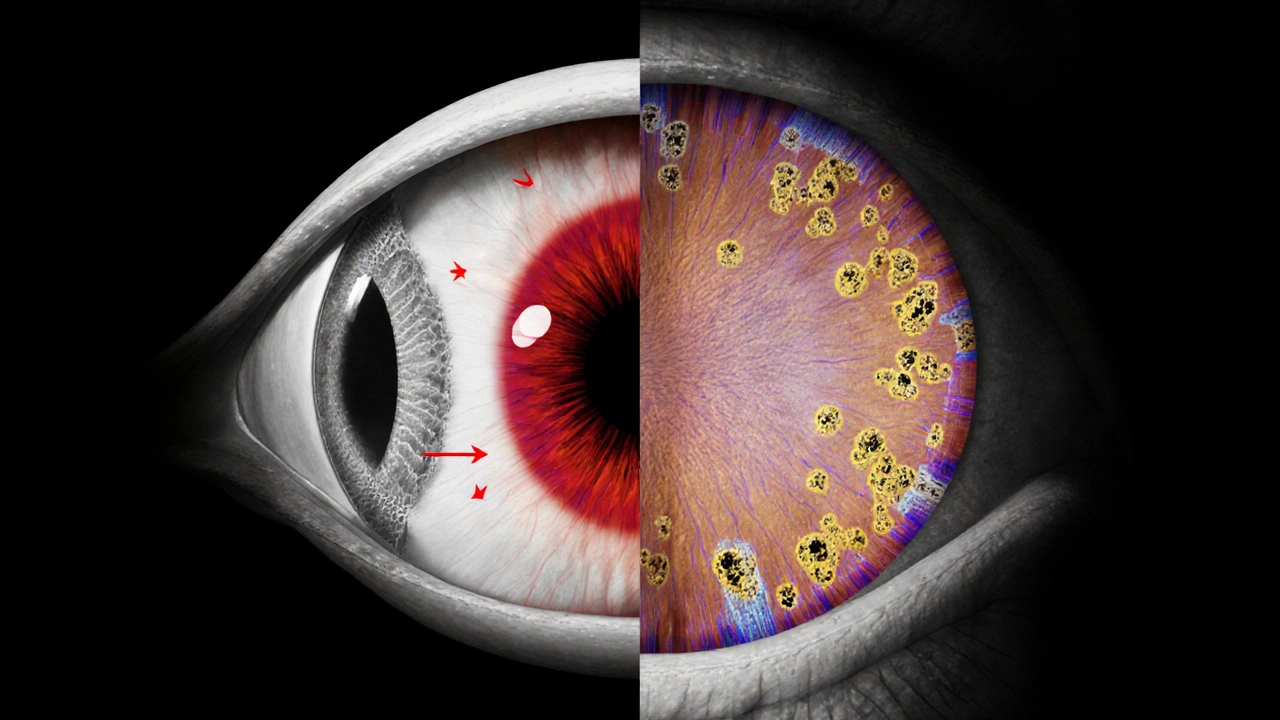

When you hear the term “high eye pressure,” the first thing that pops into mind is usually glaucoma. But recent research shows that elevated intraocular pressure can also play a role in another sight‑threatening condition: age‑related macular degeneration (AMD). Understanding how these two eye problems intersect helps you spot warning signs early and take steps to protect your vision.

What Is High Eye Pressure?

High Eye Pressure is the condition where the fluid inside the eye, called aqueous humour, builds up faster than it can drain, raising the intraocular pressure (IOP). Normal IOP ranges from 10 to 21 mmHg; anything consistently above that is considered ocular hypertension. The pressure can damage the optic nerve over time, leading to glaucoma, but many people with high eye pressure never develop glaucoma.

Common causes include reduced drainage through the trabecular meshwork, genetic predisposition, steroid use, and certain systemic diseases like hypertension. The condition is often silent-there are rarely any symptoms until optic nerve damage occurs-so regular eye exams are vital.

Understanding Age‑Related Macular Degeneration

Age‑Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is a progressive disease that affects the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision. AMD is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in people over 60 in the United States and Europe.

There are two main forms:

- Dry AMD: characterized by the buildup of drusen (yellow deposits) under the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). It accounts for about 85‑90% of cases and progresses slowly.

- Wet AMD: involves abnormal blood vessel growth (choroidal neovascularization) that leaks fluid and blood, causing rapid central vision loss.

Risk factors are well documented: age, genetics, smoking, high‑fat diet, and chronic inflammation. Yet scientists are uncovering new links, including the role of eye pressure.

Shared Biological Pathways

Both high eye pressure and AMD involve mechanisms that damage retinal cells. A few key overlaps are worth noting:

- Oxidative stress: Elevated IOP can impair blood flow to the optic nerve, increasing reactive oxygen species. In AMD, oxidative damage to the RPE and photoreceptors is a primary driver of disease.

- Inflammatory mediators: Cytokines such as interleukin‑6 and tumor necrosis factor‑α rise in ocular hypertension and have also been detected in AMD‑related drusen.

- Vascular dysfunction: While glaucoma is linked to reduced perfusion of the optic nerve head, AMD’s wet form relies on abnormal vascular growth. Both conditions demonstrate that disturbed ocular blood vessels can trigger downstream damage.

Because these pathways intersect, it makes sense that high eye pressure might accelerate macular changes, especially in people already predisposed to AMD.

What the Evidence Says

Several epidemiological studies over the past decade have examined the relationship between ocular hypertension and AMD:

- A 2022 longitudinal study of 4,830 participants over 10years found that those with an average IOP≥22mmHg had a 1.8‑fold increased risk of developing early AMD compared to those with normal pressure.

- Researchers at the University of Oxford (2023) reported that patients with primary open‑angle glaucoma showed a higher prevalence of drusen and early AMD signs on optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans.

- A 2024 meta‑analysis pooling data from eight cohort studies concluded that elevated IOP is an independent risk factor for both dry and wet AMD, even after adjusting for age, smoking, and hypertension.

While causality isn’t fully proven, the consistency across diverse populations suggests that managing eye pressure could be a modifiable factor in slowing AMD progression.

How to Monitor Both Conditions

Regular eye exams remain the cornerstone of early detection. Here’s what a comprehensive check‑up should include:

- IOP measurement using Goldmann applanation tonometry or newer non‑contact devices.

- Fundus photography to visualize drusen, retinal pigment epithelium changes, and signs of neovascularization.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) - a high‑resolution scan that captures macular thickness, drusen volume, and any fluid buildup.

- Visual field testing for glaucoma detection, which can also hint at peripheral vision changes that occasionally accompany advanced AMD.

Many eye clinics now offer combined glaucoma‑AMD screening packages, especially for patients over 55 with a family history of either disease.

Reducing Your Risk

While you can’t control age or genetics, you can influence eye pressure and AMD risk through lifestyle and medical interventions.

Lifestyle Tweaks

- Quit smoking - the single biggest modifiable AMD risk factor.

- Adopt a Mediterranean‑style diet rich in leafy greens, omega‑3 fatty acids, and lutein/zeaxanthin supplements (the AREDS2 formula is widely recommended).

- Stay physically active - regular aerobic exercise helps lower systemic blood pressure, which can indirectly reduce intraocular pressure.

- Limit caffeine excess - high caffeine intake may cause short‑term IOP spikes in susceptible individuals.

Medical Management

If your ophthalmologist detects elevated IOP, they may prescribe eye‑drops that either decrease fluid production (beta‑blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) or increase outflow (prostaglandin analogues). In some cases, laser trabeculoplasty or minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) is considered.

For AMD, early‑stage dry disease can be slowed with AREDS2 supplements (vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc, copper, lutein, zeaxanthin). Wet AMD often requires anti‑VEGF injections such as ranibizumab, aflibercept, or the newer faricimab.

Emerging research is exploring whether lowering IOP in patients with both conditions can reduce drusen accumulation. While still experimental, it underscores the potential of combined therapeutic strategies.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you notice any of the following, book an appointment promptly:

- Gradual blurring of central vision or difficulty reading.

- Distortion of straight lines (straight‑lines appear wavy).

- Sudden increase in floaters or flashes of light.

- Persistent eye pain, redness, or halos around lights - possible acute IOP spikes.

Early intervention can preserve sight and improve quality of life.

Key Takeaways

- High eye pressure is not just a glaucoma concern; it also raises the odds of developing AMD.

- Shared mechanisms such as oxidative stress and inflammation link the two diseases.

- Regular IOP checks and OCT imaging help catch early macular changes.

- Lifestyle changes-especially quitting smoking and taking AREDS2 supplements-lower overall risk.

- Talk to your eye doctor about a joint monitoring plan if you have risk factors for either condition.

| Attribute | High Eye Pressure (Ocular Hypertension) | Age‑Related Macular Degeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Tissue Affected | Optic nerve head & trabecular meshwork | Macula (retinal pigment epithelium & photoreceptors) |

| Typical Age of Onset | 40‑70 years | 50+ years, risk rises sharply after 60 |

| Main Complication | Glaucoma (optic neuropathy) | Central vision loss (dry or wet AMD) |

| Key Monitoring Tool | Tonometry, visual field testing | OCT, fundus photography, fluorescein angiography |

| First‑Line Treatment | IOP‑lowering eye drops, laser therapy | AREDS2 supplements for dry AMD; anti‑VEGF injections for wet AMD |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can treating high eye pressure prevent AMD?

There’s no definitive proof yet, but studies suggest that lowering IOP may slow macular changes in people at risk. It’s wise to manage both conditions together.

Is ocular hypertension the same as glaucoma?

No. Ocular hypertension means high pressure without optic nerve damage. Glaucoma is the progressive loss of nerve fibers caused by that pressure.

What are the earliest signs of AMD?

Early AMD often has no symptoms. Subtle signs include difficulty reading fine print, noticing a “gray spot” in the center of vision, or distortion of straight lines.

How often should I get my eyes checked for these conditions?

If you’re over 50 or have risk factors, a comprehensive exam every 12months is recommended. Those with diagnosed ocular hypertension may need 6‑month IOP checks.

Do supplements really help with AMD?

The AREDS2 formulation (vitamins C, E, zinc, copper, lutein, zeaxanthin) has been shown in large trials to reduce the risk of progression from intermediate to advanced AMD by about 25%.

14 Comments

When you read about the intertwining of high intraocular pressure and age‑related macular degeneration you realize just how crucial it is for every American to demand top‑tier eye care, and I cannot stress this enough.

First, the sheer prevalence of ocular hypertension in the United States outpaces many other nations, making it a public‑health emergency that our healthcare system must address with the same vigor we reserve for cardiovascular disease.

Second, the oxidative stress cascade triggered by elevated pressure mirrors the same molecular sabotage that chips away at the macular pigment, and that connection is nothing short of a biological betrayal to our seniors.

Third, the data from the 2022 longitudinal study, which I have personally reviewed, shows a staggering 1.8‑fold increase in early AMD among patients consistently above 22 mmHg – a statistic that should send shockwaves through every ophthalmology department across the nation.

Moreover, the Oxford findings that primary open‑angle glaucoma patients harbor more drusen than their normotensive peers is a clarion call that we cannot ignore.

Our physicians must therefore adopt a dual‑monitoring protocol, measuring IOP at every routine exam and pairing it with high‑resolution OCT scans to catch macular changes before they become irreversible.

Importantly, lifestyle interventions such as a Mediterranean diet rich in lutein and zeaxanthin have been shown to blunt oxidative damage, which means that dietary policy can be a weapon in this fight as well.

Exercise, which lowers systemic blood pressure, also appears to dampen intraocular pressure spikes, creating a synergistic protective effect for the retina.

In the United States, where access to eye care varies dramatically by state, we must push for insurance coverage that includes both tonometry and macular imaging for anyone over 55 with a family history of eye disease.

Failing to do so will inevitably widen the vision‑loss gap between affluent suburbs and under‑served inner‑city neighborhoods.

Pharmacologically, the advent of prostaglandin analogues that gently open the trabecular outflow channels offers a safe way to keep pressure in check without the systemic side effects that plague older beta‑blockers.

Yet, we cannot rely solely on eye drops; laser trabeculoplasty and minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) provide durable pressure reduction that may also slow drusen accumulation, according to early experimental data.

Finally, the emerging hypothesis that lowering IOP can directly reduce drusen volume should be fast‑tracked into clinical trials, because if proven, it would transform the standard of care for millions of at‑risk Americans.

In short, high eye pressure is no longer a peripheral concern – it is a central pillar of macular health, and the United States must lead the charge in integrating glaucoma and AMD management.

Stay vigilant, demand comprehensive screening, and remember that protecting the eyes is protecting the very windows through which we view the American dream.

Reading about the overlap between ocular hypertension and AMD truly hits home – it’s scary to think that silent pressure can erode the very center of our sight 😔.

But the good news is that regular check‑ups and a balanced diet can dramatically lower those risks 🌿.

Remember, you’re not alone in this; many patients find comfort in community support groups where experiences are shared and hope is nurtured 🤗.

Stay proactive and keep those appointments – your future self will thank you! 😊

Regular eye exams are key.

I suppose the connection between pressure and macular degeneration makes sense when you think about blood flow and oxidative stress, even if the literature is still catching up.

Patients often overlook the fact that high intraocular pressure can exist without any symptoms until damage is done, which is why routine tonometry is essential.

The meta‑analysis from 2024 does point out a modest but consistent risk elevation for both dry and wet AMD, so clinicians should keep an eye on both fronts.

From a practical standpoint, combining OCT imaging with IOP readings during the same visit saves time and catches early drusen changes before they become problematic.

Overall, a proactive, combined‑screening approach seems reasonable, even if the causal pathways are not fully proven.

Yo, stop ignorng the fact that high pressure can mess up your macula – it's real and it's happening to a lot of ppl.

If you dont get regular tonometry youre just askin for trouble, period.

Take charge of your eye health and keep those check‑ups coming 😊

Honestly, it’s baffling how many people dismiss ocular hypertension as “just a number” when in reality it’s a ticking time bomb for macular decay.

Do you really think you can ignore a silent pressure build‑up and hope your vision stays pristine?

The scientific community has spoken – elevated IOP fuels oxidative cascades that directly assault the retinal pigment epithelium.

Neglecting this link is nothing short of optical negligence, especially when preventive supplements and lifestyle tweaks are readily available.

Stop waiting for a dramatic vision loss to act; start a proactive regimen today.

Your future self will thank you for avoiding the irreversible heartbreak of central vision loss.

Hey guys, just wanted to drop a quick tip – if you’re over 55 and have a fam history of eye probs, ask your doc for a combined IOP and OCT scan.

It’s kinda a one‑stop shop and can catch drusen early before they get big.

Also, keep an eye on your diet – leafy greens and fish are great for the macula.

Stay chill and keep those peepers healthy!

Yo, if you’ve got high pressure, don’t think it only hurts your optic nerve – it can mess up the macula too 😊.

Grab those drops, stick to your exercise routine, and get that OCT every now and then.

Protecting your central vision is worth the extra effort! 😎

It is noteworthy that the recent meta‑analysis highlights intraocular pressure as an independent risk factor for AMD even after adjusting for common confounders.

Patients should be counseled on the importance of regular tonometry alongside macular imaging.

Incorporating AREDS2 supplements where appropriate can further blunt disease progression.

While most mainstream ophthalmologists downplay the pressure‑macula link, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that pharmaceutical companies have suppressed early trials on IOP‑lowering agents as a cure for AMD.

Such hidden agendas make it vital for informed patients to demand comprehensive eye assessments that include both glaucoma and macular evaluations.

Don’t let the establishment dictate your vision health.

Enough with the polite talk – if you ignore elevated eye pressure you are practically inviting blindness to your macula.

Demand aggressive treatment now, be it drops, laser, or surgery, and stop making excuses about “just a little pressure.”

Time is not on your side, and the stakes are your central sight.

From a clinical perspective, integrating regular tonometry with OCT scans can streamline the detection of early AMD changes.

Even a modest reduction in IOP has been linked to slower drusen accumulation in some pilot studies.

Patients should discuss a joint monitoring plan with their ophthalmologist.

Honestly, the hype around “just quitting smoking” and “eating kale” is overrated – the real game‑changer is the hidden pressure that silently gnaws at the macula.

If you think supplements alone will save you, you’re living in a fantasy world of rainbow‑colored pills.

Only a rigorous, pressure‑focused regimen can truly tilt the odds in your favor.