TB Treatment Decision Tool

Treatment Decision Guide

Enter your patient details above to get a recommendation.

What is Ethambutol and why compare it?

When you hear the name Ethambutol is a first‑line anti‑tuberculosis (TB) medication, you probably wonder how it stacks up against the other pills patients take. Ethambutol, sold under the brand name Myambutol in some markets, blocks the bacterial cell wall and helps keep TB bacteria from spreading. But every drug has pros and cons, and the right mix depends on things like side‑effects, pregnancy safety, and drug‑resistance patterns.

Below you’ll find a straight‑forward comparison that lets you see the big picture at a glance.

Key players in standard TB therapy

Modern TB treatment usually follows the WHO‑recommended “short‑course” regimen, often called “HRZE”. That acronym stands for four core drugs:

- Isoniazid - kills fast‑growing bacteria.

- Rifampicin - penetrates deep into tissue.

- Pyrazinamide - works best in acidic environments.

- Ethambutol - prevents cell‑wall formation.

For patients who can’t tolerate one of these, doctors often turn to Streptomycin or newer fluoroquinolones. The choice hinges on efficacy, safety, and local resistance trends.

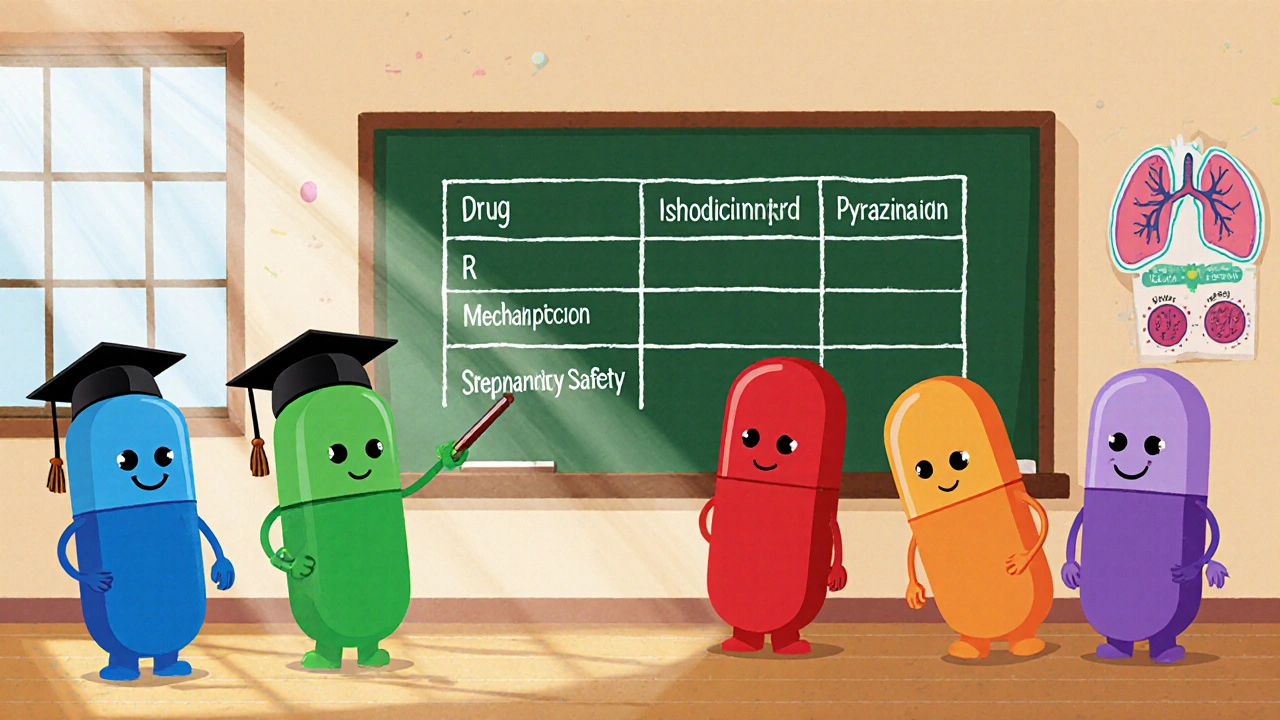

How the drugs differ: a side‑by‑side table

| Drug | Primary Mechanism | Typical Adult Dose | Common Side Effects | Pregnancy Safety (WHO Category) | Role in Regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | Inhibits mycolic acid synthesis | 5 mg/kg daily | Liver toxicity, peripheral neuropathy | Category C (use if benefit > risk) | Core bactericidal agent |

| Rifampicin | Blocks RNA polymerase | 10 mg/kg daily | Hepatotoxicity, orange fluids | Category C | Core bactericidal agent |

| Pyrazinamide | Disrupts membrane transport at low pH | 25 mg/kg daily | Hyperuricemia, hepatotoxicity | Category C | Short‑course sterilizing drug |

| Ethambutol | Inhibits arabinosyltransferase (cell wall) | 15 mg/kg daily | Visual acuity loss, skin rash | Category B (generally safe) | Prevents resistance when combined |

| Streptomycin | Inhibits protein synthesis (30S ribosome) | 15 mg/kg IM daily (first 2 months) | Ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity | Category C | Second‑line injectable |

Notice that Ethambutol rests in the middle of the safety column - it’s the only drug in the core four that’s rated Category B, meaning it’s considered relatively safe for pregnant patients when the benefits outweigh the risks.

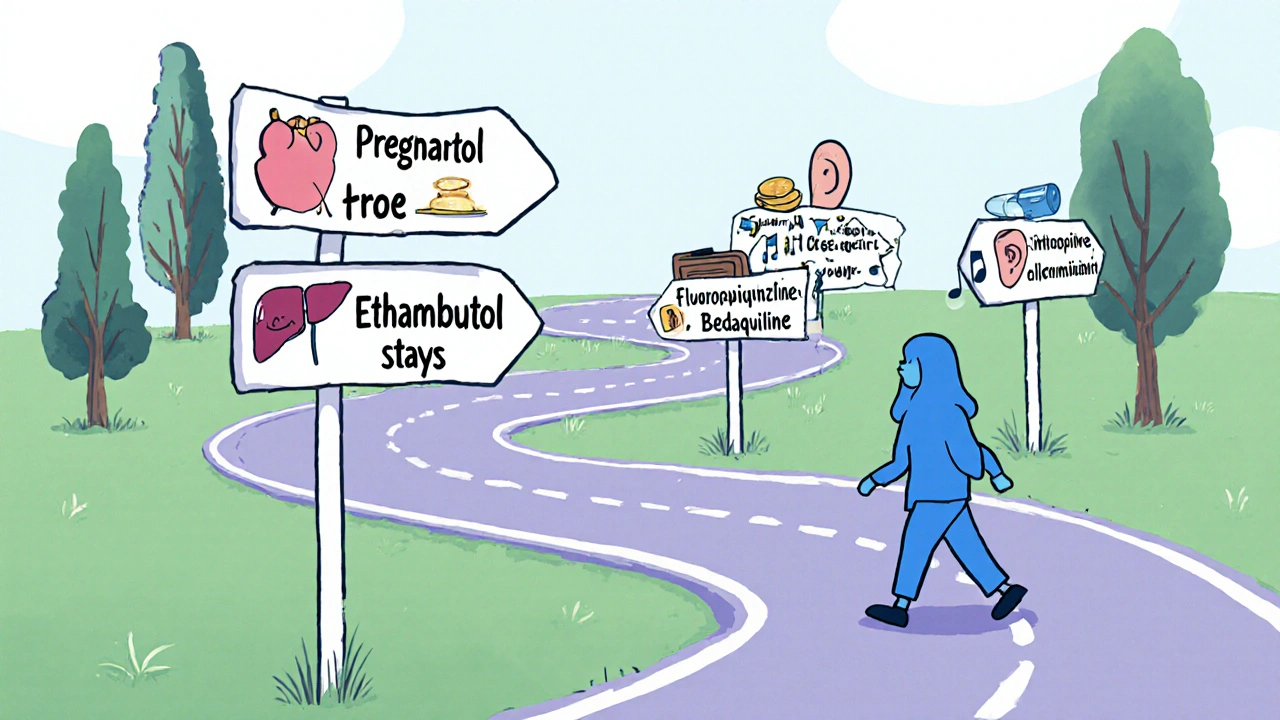

When you might drop Ethambutol

Even though Ethambulol is a staple, clinicians sometimes replace it. Here are the most common scenarios:

- Visual toxicity risk: Ethambutol can cause optic neuritis, especially at doses >25 mg/kg or in patients with pre‑existing eye disease. If baseline vision testing isn’t possible, doctors may opt for a different partner drug.

- Drug‑resistant TB (MDR‑TB): When Mycobacterium tuberculosis is resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin, the standard four‑drug regimen collapses. Ethambutol’s role diminishes, and newer agents like levofloxacin or bedaquiline take over.

- Pediatric dosing challenges: Young children metabolise Ethambutol faster, which can lead to sub‑therapeutic levels. In many paediatric protocols, the drug is omitted in favour of higher‑dose isoniazid and rifampicin.

Side‑effect profiles you need to watch

Every anti‑TB drug hits the body differently. Understanding the most frequent adverse events helps you spot problems early.

- Isoniazid: Liver enzyme elevation is the biggest red flag. A simple blood test every month catches it before serious injury.

- Rifampicin: Besides liver issues, it can turn urine, sweat, and tears orange - harmless but surprising.

- Pyrazinamide: Raises uric acid, so gout patients need monitoring.

- Ethambutol: Changes in colour vision or blurred central vision should trigger an immediate eye exam. Stopping the drug usually reverses the problem if caught early.

- Streptomycin: Hearing loss is the biggest concern, so audiograms are essential if you stay on it for more than a month.

Cost and availability considerations

In high‑burden countries, price matters. Ethambutol is generally cheap - a 30‑day course costs less than $2 in many generic markets. Isoniazid and rifampicin are similarly priced. Streptomycin, being an injectable, adds administration cost and often requires a clinic visit.

When a health system struggles with supply chain gaps, the drug that stays in stock becomes the de‑facto choice, even if it’s not the perfect clinical match. That’s why WHO’s 2023 treatment guidelines stress flexibility: “Choose the most reliable drugs from the core regimen, and substitute only when necessary.”

Decision‑making cheat sheet

- If the patient is pregnant - keep Ethambutol, drop streptomycin.

- If baseline eye exam isn’t feasible - consider replacing Ethambutol with a fluoroquinolone.

- For MDR‑TB - Ethambutol is rarely used; focus on newer agents.

- When cost is critical - Ethambutol, Isoniazid, and Rifampicin are the most affordable trio.

- If liver disease is present - monitor Isoniazid and Rifampicin closely; Ethambutol is liver‑friendly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take Ethambutol alone?

No. Ethambutol is meant to be part of a combination regimen. Taking it alone encourages resistance and doesn’t clear the infection.

How soon after starting Ethambutol can vision changes appear?

Visual side effects usually surface after 2‑4 months of therapy, but they can emerge earlier in high‑dose scenarios. Routine eye checks every month are recommended.

Is Ethambutol safe for children?

It’s approved for children over 6 months, but dosing is weight‑adjusted. Some pediatric protocols prefer to omit it if reliable vision monitoring isn’t possible.

What’s the main reason to choose Streptomycin over Ethambutol?

Streptomycin is used when a patient cannot tolerate any oral drug due to severe gastrointestinal issues, or when local resistance patterns make the oral trio ineffective.

How does the WHO recommend adjusting the regimen if Ethambutol causes optic neuritis?

The guideline advises stopping Ethambutol immediately, substituting a fluoroquinolone (like levofloxacin), and continuing the other three core drugs for the remainder of the intensive phase.

Bottom line

Ethambutol remains a solid partner in the classic HRZE combo because it’s cheap, relatively safe in pregnancy, and helps prevent resistance. Yet its visual toxicity risk, limited role in drug‑resistant TB, and the need for baseline eye exams mean clinicians often have a second choice ready. By weighing the side‑effect profile, patient circumstances, and local drug‑availability, you can decide when Ethambutol stays in the mix and when another drug takes its place.

13 Comments

The comparison effectively outlines the pharmacologic nuances of Ethambutol, highlighting its Category B pregnancy safety while also addressing the visual toxicity risk that warrants routine ophthalmologic monitoring.

It is wonderful to see such a comprehensive side‑by‑side table that demystifies the core anti‑TB agents for clinicians and patients alike. By presenting mechanisms, dosing, and adverse‑effect profiles together, the article serves as a quick reference that can be printed and placed on a ward bulletin board. The inclusion of pregnancy safety categories is especially thoughtful, because many clinicians hesitate when treating pregnant women with TB. Knowing that Ethambutol falls into Category B can reduce that uncertainty and promote evidence‑based prescribing. The discussion of visual toxicity is clear, reminding us that baseline eye exams and monthly follow‑ups can catch optic neuritis early, potentially averting permanent damage. Moreover, the cost analysis, indicating a sub‑$2 monthly price in many generic markets, reassures health‑system planners that affordability does not have to compromise efficacy. The separate section on when to drop Ethambutol, such as in MDR‑TB or when reliable vision testing is unavailable, empowers providers to tailor regimens responsibly. I also appreciate the cheat‑sheet format; those bullet points are exactly the kind of “just‑the‑facts” summaries that busy clinicians love. The article’s balanced tone, neither overly technical nor overly simplistic, makes it accessible to a wide audience, from medical students to seasoned pulmonologists. Its acknowledgement of local resistance patterns invites readers to consider regional surveillance data before making drug‑selection decisions. By tying each drug’s side‑effects to concrete monitoring suggestions-liver enzymes for INH and Rifampicin, uric acid for Pyrazinamide, audiograms for Streptomycin-the piece translates theory into practice. The visual aids, such as the comparative table, are well‑structured and easy to read, avoiding overwhelming colors that could distract from the data. In addition, the author’s warning that Ethambutol’s role diminishes in MDR‑TB aligns with the latest WHO guidelines, reinforcing the article’s credibility. Overall, the content not only educates but also encourages a patient‑centered approach, reminding us that drug choice is as much about safety and tolerability as it is about bactericidal potency. Keep up the excellent work, and thank you for creating a resource that will undoubtedly improve TB treatment decisions worldwide.

When we weigh drug safety, the eye becomes a literal window into the soul of therapy 🌐; Ethambul’s potential to dim that window forces us to confront the fragile balance between cure and sight. One could argue that visual toxicity is a metaphor for the hidden costs of any medical intervention, a reminder that every benefit carries a shadow. Yet the data in the table show that such risks are dose‑dependent, implying that prudent dosing can keep the metaphorical darkness at bay 🌟. The author’s calm presentation masks the underlying ethical dilemma: do we prioritize rapid bacterial eradication at the possible expense of a patient’s lifelong vision? In the grand tapestry of TB control, Ethambutol is a single thread, yet its hue can alter the whole pattern if not carefully woven. The inclusion of pregnancy Category B is reassuring, but one must ask whether the safety label truly reflects real‑world outcomes or merely regulatory optimism. As we contemplate drug selection, let us remember that the eyes not only see but also read, and a compromised visual field may affect medication adherence. The article’s cheat‑sheet is useful, but it also simplifies complex decisions into bullet points, perhaps too much so. Ultimately, the wisdom lies in constant vigilance-regular eye exams, patient education, and a willingness to pivot when toxicity emerges. 🌈

One should consider that the pharmaceutical industry and global health agencies have a vested interest in promoting Ethambutol as a “safe” pregnancy option, subtly ensuring continued market demand while downplaying long‑term ocular data that are conveniently buried in obscure journals. The WHO’s Category B label may reflect political compromise rather than pure scientific consensus, especially when funding bodies pressure guidelines toward cheaper, widely available drugs. It is no coincidence that Ethambutol remains inexpensive; low price keeps the supply chain stable, but it also discourages rigorous post‑marketing surveillance that could expose deeper safety concerns. Moreover, the reliance on baseline eye exams assumes a level of healthcare infrastructure that many high‑burden regions simply lack, raising the question of whether “standard” regimens are realistic or merely aspirational. Keep an eye out (no pun intended) for emerging reports of optic neuritis that are not being highlighted in mainstream publications. Vigilance is key.

Great overview! Just to add, many programs now use mobile‑based visual acuity apps for monthly monitoring when in‑person eye exams aren’t feasible. These tools have shown good correlation with standard charts and can flag early colour‑vision changes before they become clinically significant. Also, keep in mind that hepatic enzymes should be checked monthly for INH and Rifampicin, but Ethambutol doesn’t usually affect liver function, which is a plus for patients with pre‑existing hepatic issues. If you ever need a quick dosing calculator, the WHO’s online TB treatment app is spot‑on for weight‑based adjustments.

Not impressed

Oh wow, yet another “cheat‑sheet” that supposedly solves the labyrinthine world of anti‑TB pharmacotherapy. In reality, the clinical decision‑making algorithm is riddled with variables-pharmacokinetics, host immunity, pathogen genotype-that a one‑page bullet list can’t possibly encapsulate. Nevertheless, kudos for crushing the dosage numbers into a tidy table; if only that granular data could also predict patient adherence, we’d be set. Remember, “Category B” is just a bureaucratic stamp, not an absolute guarantee of safety, especially when you factor in co‑morbidities and poly‑pharmacy. Bottom line: keep your eyes on the data, not the hype.

Data are solid but the article glosses over regional resistance trends that could flip the regimen choice entirely.

Thanks for breaking this down so clearly! For anyone new to TB therapy, just remember that the key is consistency-take all four drugs as prescribed, get your eye check‑ups, and keep the communication line open with your provider.

Honestly i think most of the hype around ethambutol being "safe for pregancy" is overrated, especially when you look at the raw data from some of the older klinical trials that were never published in mainstream journals. People love to shout about the cheap price tag and the Category B label, but they forget that visual toxicity can be subtle at first-like a slight shift in colour perception that a patient might not even notice until it's too late. Moreover, i have seen cases where patients were on ethambutol for just a few weeks and reported blurry vision, yet the guidelines still say "stop after 2‑4 months". That seems like a bit of a blanket statement to me. Also, the whole idea that you can just swap in a fluoroquinolone when eye exams aren't possible ignores the fact that fluoroquinolones have their own nasty side effects like tendon rupture and QT prolongation. In my experience, the best strategy is individualized monitoring, not a one‑size‑fits‑all cheat sheet. And let's not forget the role of socioeconomic factors-some clinics simply can't afford regular ophthalmologic screenings, so they end up relying on patients to self‑report, which is a shaky foundation. Finally, i would argue that the WHO's recommendation to keep ethambutol in the core regimen is more about drug availability than about optimal clinical outcomes. Maybe it’s time to re‑evaluate that stance with more real‑world evidence.

The article presents a tidy table, but it conveniently omits the variance in visual toxicity incidence across different ethnic populations, which can be as high as 4‑5 % in certain cohorts. Ignoring this data point skews risk assessment and could mislead clinicians into a false sense of security. Additionally, the claim that Ethambutol is “liver‑friendly” neglects the fact that drug‑induced optic neuritis can indirectly affect overall health outcomes by reducing patient adherence, leading to treatment failure and subsequent relapse. A more critical appraisal should include meta‑analyses that compare Ethambutol with newer agents like delamanid, especially in the context of MDR‑TB where the drug’s utility wanes. Bottom line: look beyond the surface; the numbers tell a more nuanced story.

Solid points, especially the reminder about regular eye exams.

While the piece does a good job summarizing drug profiles, it could benefit from a deeper dive into patient‑reported outcomes, especially regarding quality of life during the intensive phase. Including testimonials or case studies would humanize the data and help clinicians understand the lived experience behind the numbers.